Cards FOR HUMANITY

Harnessing the natural flow of conversation and human inclination towards play to encourage innovative and unexpected methods of collaboration.

Na

vi

ga

tion

.

.

Design for Health: Corporeal Studio (OCADu)

TEAM

graphics, research, report writing

ROLE

photoshop, illustrator

tools

Challenge

Wicked Problems are complex issues that are difficult to solve because of their volatility and the degree to which they’re embedded in society and entangled with other wicked problems. Because of their contentious nature, even simply discussing wicked problems often ends in more cynicism.

SOLUTION

Cards for Humanity (C4H) is a discussion-based card game of free-flowing dialogue, societal interrogation, and strengthened empathy. Within a framework of prompts and personas, it encourages players to collaborate with each other in innovative and unexpected ways to interrogate wicked problems.

The end goal isn’t necessarily to fix these issues, but rather to comprehend them and the actors that impact them.

note that: persona icon designs are by collaborator Katherine Valenzuela

process

gamification

We have a natural inclination towards play that persists with us from childhood throughout the rest of our lives. Games are often competitive, but many are collaborative, too.

C4H ponders whether a game that revolves around social pitfalls can be collaborative, or if players will emerge with the cynicism common in competitive gaming.

GAME design development

C4H is designed around simple mechanics, allowing players to put most of their effort towards complex discussions.

The main challenge of developing a game built around discussion was echochambers/groupthink or dissent for dissent’s sake. It seems likely that the people interested in picking up a game that addresses wicked problems would be a) already similarly-minded individuals, or b) willful contrarians (think internet trolls).

The point of this tool needed to be about a) collaborative problem-solving, but also about b) understanding others’ perspectives and reasoning, even when we don’t agree with them.

As such, we implemented a roleplaying mechanic, with a pre-determined set of personas. The personas give players a set of values, motivations, and modes of action with which to contribute to and interpret dialogue.

graphic design development

The visual design mirrors the core concept of C4H. Six colours from across the visible spectrum for six players with unique life experiences. Organic patterns and shapes for organic ideas and discussions. Sleek and minimal 2D graphics that allow projection and extrapolation without the constraint of preconceived rendering.

LOGO

The words are reversed and flipped, symbolic of ideas being turned inside out and reworked. No matter which direction you read the logo from, it’s still coherent. Additionally, when rotated, the logo can also read “Humanity for Cards” which sounds silly at first, but the reality is that because of wicked problems, so many people don’t even have the kind of leisure time that C4H asks of its players.

COLOURS

Each colour is distinct from its peers, but all with slightly muted tint to create harmony that approaches the pastel precipice. This represents our ability to form community in the midst of our human individuality. In addition, we chose not to use an absolute black, which is symbolic of how the world doesn’t function in absolutes.

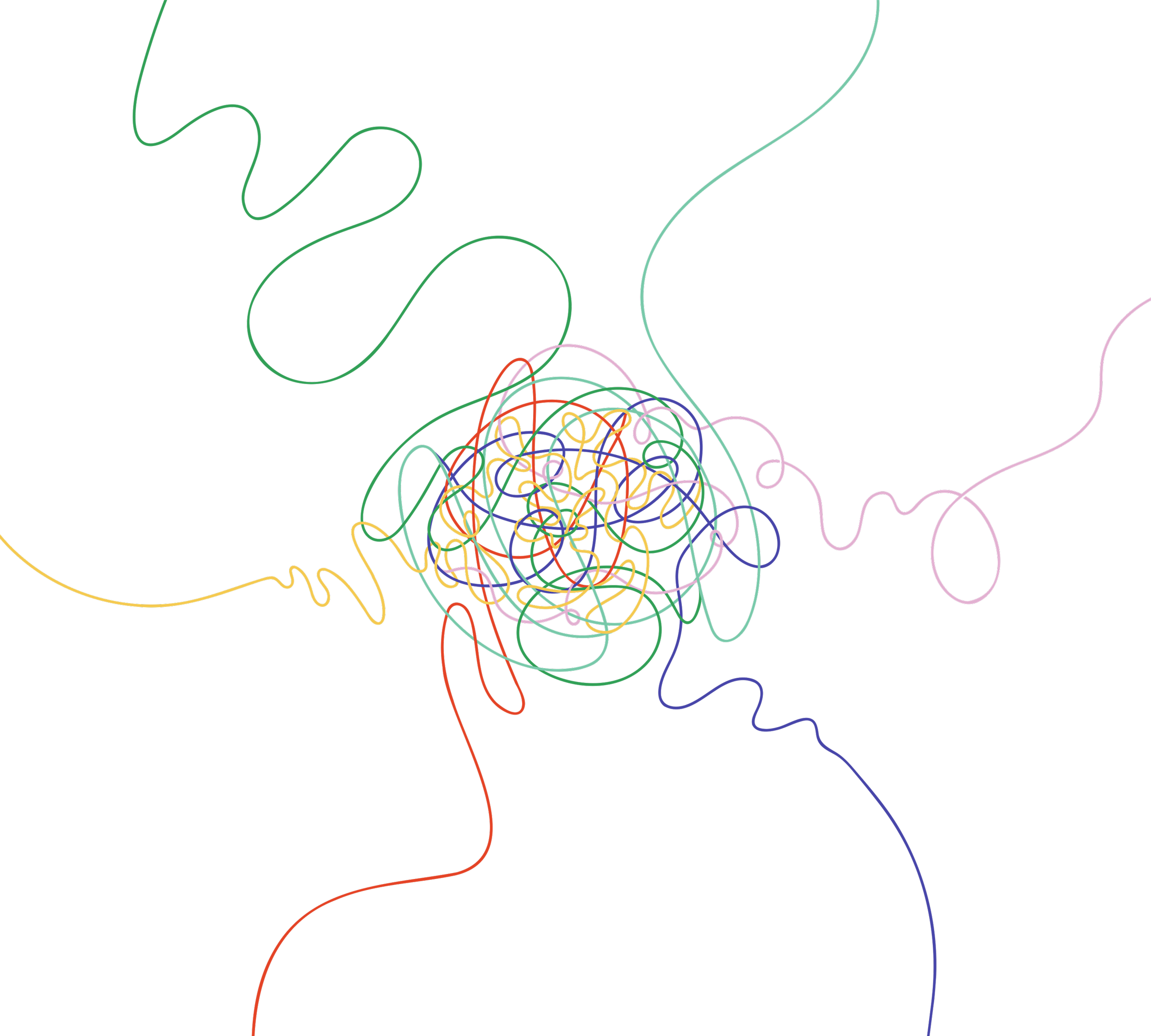

PATTERNS

The tangle pattern, used for Story cards, represents both complexity and individuality of thought, as well as the confusion and interwovenness of wicked problems. They’re so embedded in society that they’re impossible to unravel on our own, but get too many cooks in the kitchen trying to do things their own way, and we just end up tugging the knot tighter. In order to approach these problems, we need to work cooperatively.

Additionally, each strand follows its’ respective persona’s MO: the Child investigating everything, the Caregiver’s sweeping support, the Sage’s powerful motivation, the Shadow circling every nook and cranny, the Bureaucrat finding common ground, and the Innovator finding all sorts of connections.

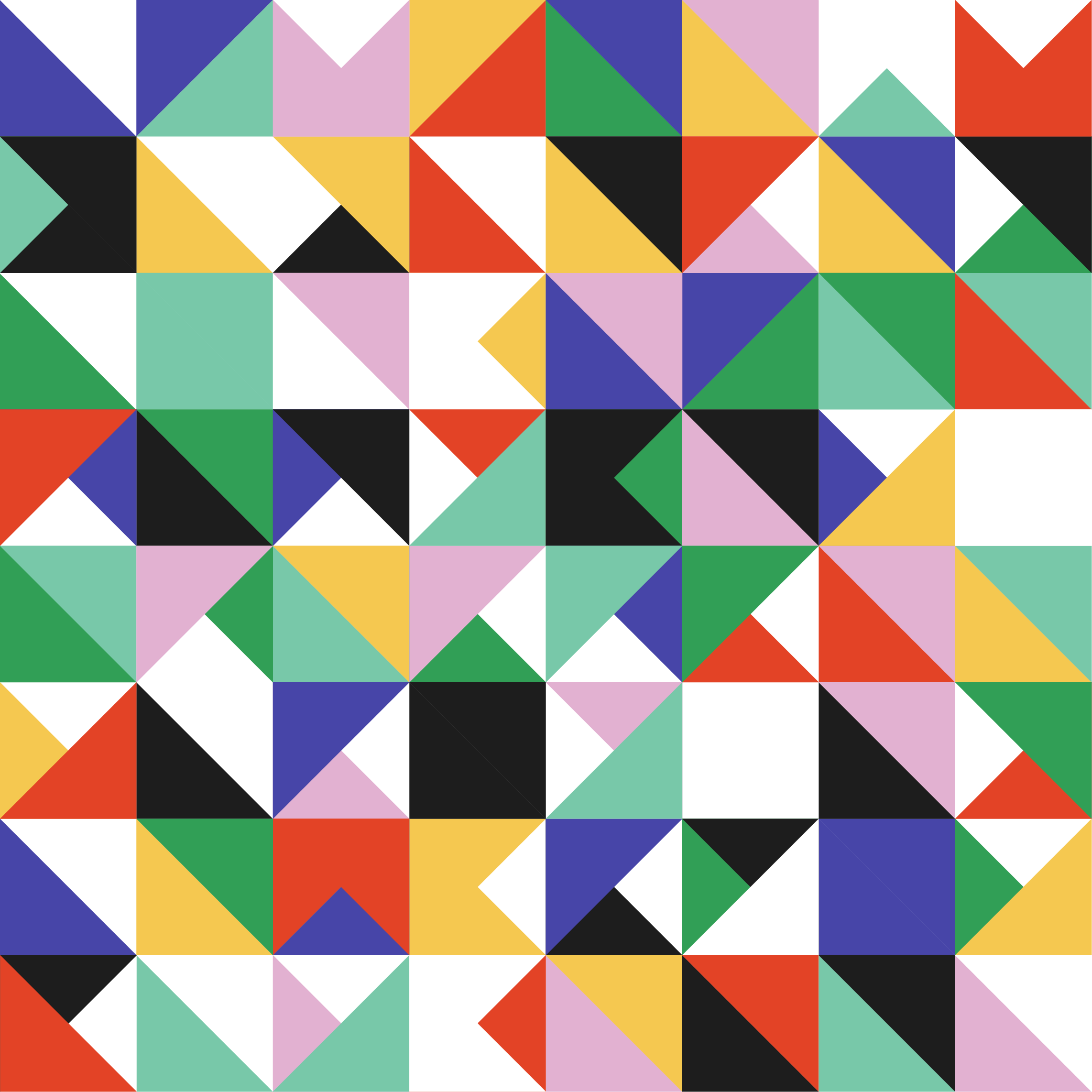

The mosaic pattern, used for Task cards, symbolizes diversity of thought. Each tile connects two or more colours, plus the black and white accent shades, in non-uniform ways. No two tiles are the same, and their arrangement isn’t methodical, yet they still come together to form an array of angles and ideas. The pattern itself is repeatable, illustrating how massive the diverse social mosaic we live in can be.

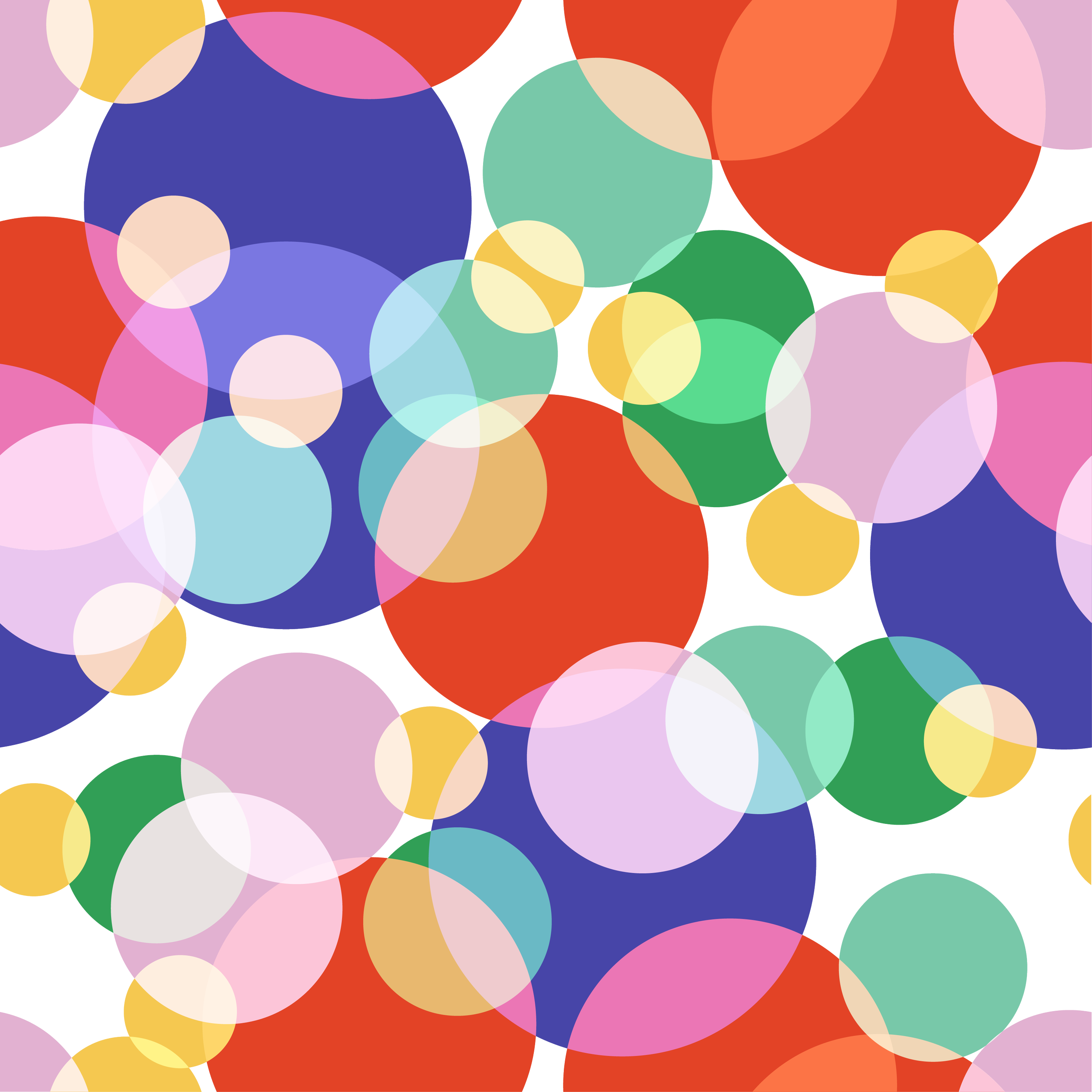

The bubble pattern, used for Question cards, is representative of overlapping ideas and the potential for that convergence to be a source of inspiration for something new. Sometimes the bubbles maintain their original colour, and sometimes the infusion of a new element changes the entire concept.

background Theory & research

-

Adversarial Design is a type of design that evokes and engages political issues, and Agonism is a political theory that emphasizes potentially positive aspects of certain forms of political conflict. Wicked Problems often are political, and with them at the core of our design, we certainly needed to know how to emphasize the positives of disagreement.

-

The point of Bohm Dialogue is not to defend your own opinions or to make trades of information and influence others, but to listen with sympathy and interest and to understand others’ positions and to be open to changing your own point of view.

Bohm emphasized that in order to create a coherent culture, it required dialogue between different subcultures where they could share their own meanings in order to create new meanings together.

-

Critical Design is an attitude. In can be speculative, conceptual, provocative, and itcan be darkly satirical. It’s not looking for a solution as much as it’s looking to identify a problem and provoke discussion. Critical Design asks, “What if?”, but it isn’t asking about benefits the future could bring like an orthodox design method would. It’s asking “What if we allow this problem to keep going unchecked?”, creating often satirically horrific visions of the future.

-

Co-design is an approach to design that’s concerned with getting stakeholders (such as community members) involved as equal collaborators. Co-design prizes lived experience and the perspective of every end-user it can get its hands on as it tries to design a solution that actually functions intuitively for the people it’s intended for.

-

Design Thinking is a non-linear process that involves many iterations of an idea, and often many ideas themselves. It allows for a robust ideation process that overlaps with its other phases which include emphasizing, defining, prototyping, and testing. Design thinking circles back on itself frequently, allowing for free and grand ideation without constraint (otherwise known as spitballin’).

-

Game Theory is a quantitative way of examining social interaction, and can also provide theoretical insights on cooperation. Using Game Theory’s Shapley Value, (the method of dividing up costs in cooperative games), alongside socially critical design philosophies like adversarial design and critical design, can illustrate where we fall short in collaboration and fair contributions.

Game Theory gave us our definition of a game as "any interaction between people in which each person’s payoff is affected by the decisions made by others".

-

Gamification is the process of adding game mechanics into concepts, designs, and environments that are traditionally not games. Gamification can make these environments more engaging and can allow for more directed outcomes by setting up conditions of play (aka.. The Rules of The Game).

-

Just like the name implies, Participatory Action Research (PAR) emphasizes participation and action. It seeks to make sense of the world through collective efforts to transform it. PAR’s main tenet of collective inquiry aims to lead to social change through experimentation grounded in experience and social history.

-

The Pluriverse is a condition in which many worlds fit in. Based on Arturto Escobar’s 2018 book, Designs for the Pluriverse, the concept of the Pluriverse embraces the notion of differences – biological difference, cultural difference, ontological difference. Designing for the Pluriverse is about creating cultural meanings and practices, experiences, and particular ways of living.

END NOTES

You might be wondering if C4H is actually playable. Have we played it? Yes, absolutely—all throughout development and beyond. Is it available for you to play? Well… not really. As a class project from our first semester, we noticed several kinks after completion but never had the chance to sit down and work them out (at which point, in the spirit of iterative design, we would probably end up re-designing half the thing).

Dialogue and communication remain free and accessible to many of us, so I would encourage you to play some version of C4H if you’re feeling so inclined.

Note number two: yes, the name is indeed derived from the infamous card game that comes in a little black box. Aside from being word/speech-based card games, the two don’t really have much to do with each other, though.